Flux Capacitor

Building software is great. You can literally create something out of nothing and change the world.

Some ideas can be realised very quickly too. If your idea needs a website and basic webshop, you could be up and running in a day. But if your needs are a little more demanding, the time required to launch a new product, feature or even bug fix tends to be significant. Most of that time is not spent on problems unique to your company. In fact, most companies we developed for, struggle with the exact same technical problems.

We don’t believe it has to be this way. Many of these technical problems can be solved much better by a dedicated service maintained outside your company. This way, you can focus on the actual challenges in your domain and build significantly faster and better.

Messaging as a Service

One of the biggest problem areas in the microservice era, is service to service communication. Our objective is to make it easy, fast and reliable for your services to message each other and the outside world. We don’t want you to worry about building the next microservice platform like so many companies have before you, just so you can launch your next big thing.

We’ve developed a specialized service that enables highly performant, reliable messaging between applications. It makes it a breeze to launch new services. Once a service is connected to Flux Capacitor it can talk to any other connected service. Your service doesn’t need any proxy, load balancer, firewall, service registry, api gateway, circuit breaker, message queue, etc. to accomplish that. And if your service is getting too busy to handle all requests you can just add a second instance; Flux Capacitor will automatically balance the request load.

Integrating with Flux Capacitor

Data between client applications and Flux Capacitor is communicated over websockets. The service has a variety of websocket endpoints, serving different needs. If you connect from a Java application you should include our Java client as a dependency. By passing the URL of the Flux Capacitor service you want to connect with, the client will automatically set up and maintain all web socket connections to the service.

Much of the data sent to and from Flux Capacitor is in the form of messages. A message consists of a serialized payload, some client metadata (containing e.g., information about the customer that caused the message), and some message headers used by Flux Capacitor for message routing.

Data sent to and from Flux Capacitor is often batched and compressed aggressively for highest throughput. This way Flux Capacitor can store and pass along messages at rates of hundreds of thousands to a few million messages per second.

Messages only get batched if it doesn’t come at the cost of latency though. Once a message is published we aim to get it in the hands of willing consumers as fast as possible. The latency between the time a message gets produced and consumed is typically in the order of a few milliseconds depending on the backlog of that consumer.

Core concepts

Message routing

Commands and Queries

Most applications communicate by sending API calls to each other. The majority of these calls are either queries or commands. A query is a request for information, like: “Give me all the orders that shipped last month”. In web APIs a query is typically performed via a GET request. A command is a request for the application to do something, for instance “Send an order”, “Delete an order”, etc. In web APIs these are usually the POST, PUT and DELETE requests.

These web API calls and other forms of direct communication do not scale well for rapidly-changing applications with high performance demands. For high availability and scalability, services are typically deployed more than once. A load balancer is then used to balance load and handle failover. Proxies and components like api gateway are often used to route or modify specific API requests. As the numbers of endpoints grow you’ll also need something like a service registry. Besides having all this infrastructure, you’ll also have directly exposed endpoints. These need to be secured with even more infrastructure, like a firewall and DDoS protections. You will need a dedicated team of cloud engineers to deal with all these concerns before you’re even ready to launch your product.

Typical microservice infrastructure. Source

This additional infrastructure is the result of the fact that queries and commands are being pushed to your services. What if we would turn this around? What if your services would pull in their queries and commands from a central message broker and handle them at their own pace? This simple change would render all the mentioned infrastructure obsolete. Moreover, we would break the link between the producer of a request and its consumer. The producer does not need to know anything about the consumer (location transparency) and vice versa. The only thing your application needs to know is what queries or commands it wants to handle.

With Flux Capacitor this indirect form of communication based on pull instead of push is made very easy. We provide your applications with a single endpoint, to which your services can both publish and subscribe. For instance, if you need to send a query to another service (or your own), you will be able to do it with this single line of code:

List<Order> orders = FluxCapacitor.queryAndWait(new GetOrders(...));

Note: examples here are in Java, but obviously Flux Capacitor does not care what language your applications are written in. To send a command you can simply do:

FluxCapacitor.sendCommand(new PlaceOrder(...));

The results of your command or query will be returned to you, so it would be just as if you invoked a method within your application. And if your action causes an exception somewhere, the exception will be thrown to you as well.

To handle a request, all you need to do is add a Handler, which is a function that takes a request as input, and gives a result as output. For instance:

@HandleQuery

List<Order> handle(GetOrders query) {

return...;

}

As you see, you’ll still need to implement the behavior that’s specific to your business, but all the technicalities of connecting services are no longer your concern.

Tracking

The process of pulling messages from Flux Capacitor is called tracking. Messages published to Flux Capacitor are placed into a variety of message logs depending on the function of a message. There are different logs for commands, queries, results (i.e. responses to commands and queries), events, and scheduled messages. There are also logs for non-functional messages containing things like application metrics and errors.

Flux Capacitor will retain messages in these logs for a significant amount of time. By default, events are retained for eternity, while application metrics are only retained for one month. Before a message is made available for consumption it will be persisted by our data store. That means every message is available for auditing and consumption even days (or years) after it’s been produced.

If a message gets consumed it will not be removed from the message log. In fact, most messages will be pulled many times by a variety of consumers. This makes a message log far superior to the more familiar message queue, which typically contains messages only until they get consumed.

The process of message tracking works as follows:

- A tracker requests its next batch of (up to N) messages

- The tracker processes these messages

- The tracker updates its position in the log (this is often the index of last message it processed)

When there are messages waiting, your tracker will immediately get a batch that’s never larger than a chosen maximum size. When there are no messages available, the request will wait; any new messages will be sent instantly once they have been persisted.

The process of sending a query and getting back the result actually involves two trackers: one that processes queries and one that processes results (running in the application that sent the query). Below is an image that illustrates the process.

![]()

How a service can query another using tracking.

With tracking, it is not possible to overwhelm your application with too many requests because your trackers decide how many messages they consume (i.e., trackers can apply backpressure). This way your service cannot fall victim to e.g., a denial-of-service attack, because your application is always in control of what it receives.

Another benefit of tracking is that it’s not possible to ‘miss’ a message. With queues, messages often disappear once read, and there are certain limitations set for how long a message remains available. As trackers are in command of their own position in the message log (step 3 above), they will always continue tracking at the point where they left off. Even in the event of an application crash during processing (i.e., in step 2), a tracker never misses a message. In that case, the application has not updated its position yet, so it will simply receive those messages again once it has restarted. If the consumer is distributed over multiple nodes you don’t even need to wait that long: Flux Capacitor will automatically pass the messages to trackers running on the other nodes.

Consumers

You can configure how messages get tracked and processed using consumers. A consumer is a logical part of your application that runs isolated from other consumers. It defines:

- What message type to fetch (e.g., events)

- How many messages to fetch and what payload types

- How messages are handled, usually by selecting handler classes (e.g., all handlers in this package)

- How many trackers to use in parallel (e.g., 4 trackers per application instance)

Most importantly, consumers each define a unique name, so Flux Capacitor can distinguish them from other consumers and distribute all messages correctly.

Trackers pass the messages they receive on to their handlers. Trackers belonging to the same consumer can be seen as separate Threads of the consumer. The main function of running multiple trackers per consumer (i.e., running multi-threaded) is load balancing and redundancy.

In most cases you’ll configure multiple consumers per application. Because consumers are isolated from other consumers it does not really matter if they live together in the same application or in separately hosted applications; their behavior and interaction remains exactly the same. That means, you can divide parts of your application that do not really belong together, before you even move them to a separate application. Whether to split up one service into multiple services (often a question of much headache with microservices) is a question you can very easily postpone until you know for sure.

Consumers can be split into separate applications without changing the way they communicate

Say you have a shop application, with orders and deliveries, and you need to integrate with a delivery provider like UPS. You don’t want you core code influenced by this integration, but you also don’t want to split up your git repo because that would be a hassle for the development team. With isolated consumers there’s no need. You can put all UPS related handlers in a separate consumer. The UPS consumer might have handlers listening to events from your core consumer, but whether the consumer is inside the same application or not, does not matter one bit. And once you decide that another team is going to deal with the UPS integration you can simply split up the git repo then and launch a new application.

Quite often, programmers will join separate concerns that have no business being joined at all. These cross-cutting concerns often even get mixed with the core of your application. By allowing separate consumers, you can easily listen to a whole bunch of messages separately, and easily remove these cross-cutting concerns from core functionality.

Creating a new consumer is easy. Here is an example in Java that configures a new consumer that handles queries of shop orders in Spring:

@Configuration

class Config {

@Autowired

void configure(FluxCapacitorBuilder builder) {

builder.addConsumerConfiguration(ConsumerConfiguration.builder()

.name("OrderQueryConsumer")

.messageType(QUERY).threads(2)

.handlerFilter(h -> h.getClass().getPackage().getName()

.startsWith("com.example.orders"))

.build());

}

}

If a handler is not selected by any of these custom consumers, it is assigned to a default consumer of the application. I.e., you never need to worry that you will miss messages if handlers are not part of any custom consumer.

High availability and load balancing

Of course, it is of vital importance that your services are highly available. Flux Capacitor will automatically balance messages between all available trackers of your applications. It doesn’t matter if one of your instances shuts down or another one starts up: the load will immediately be redistributed without the need of any dedicated load balancer.

What’s more, messages are distributed across trackers predictably. That is, each message gets assigned a Segment (more on that later). By default, Flux Capacitor uses 1024 segments. When a consumer consists of two trackers, segments are divided 50-50. Trackers only get messages from their assigned segments, and trackers only update their log positions for the segments to which they have been assigned.

Each tracker within a consumer is assigned messages from segments equally.

When you add additional trackers (usually during deployment of your application), the trackers will take over segments of existing trackers (once they have finished processing their current batch). Naturally, Flux Capacitor takes care of this automatically. When you remove a node, Flux Capacitor disconnects its trackers immediately and releases their segments to the other available trackers.

By default, messages are assigned a random segment, which is a hash of their unique message id. However, you can also define the message segment yourself. Our Java client can even do this for you automatically. All you need to do is to annotate the Routing key in your message payload:

class CreateOrder {

@RoutingKey

String orderId;

}

Selecting a routing key is useful because it ensures that messages about the same subject (in this case the same shop order) get assigned the same segment, and thus get processed by the same tracker. This allows you to build up a local cache of order entities for instance. Also it guarantees that messages about the same subject are handled in the correct order.

Time travel

For fans of ‘Back to the Future’ it should come as no surprise that Flux Capacitor makes time travel possible.

As we retain messages for a long time, you can reset a consumer to any point in time (even a time in the future), or instruct new consumers to start tracking from the beginning of the log.

Revisiting old events can be very useful. Say, you want to introduce a new consumer that creates management reports. This is typically not something you want to be working on at the start of your project. By having the consumer revisit all past events it will be able to build management reports retroactively. You could say that this feature allows you to be a lot more agile as you develop your product: no need to plan out every nook and cranny of your product, but just build it when the need is there.

Resetting a pre-existing consumer can also very useful. Suppose you need to replay events because your application contained a bug for a while that made it process a bunch of messages wrongly. Simply deploy your fix, then reset the consumer to a time before the bug and like that all messages will be processed again, now with the fixed message handlers. This has been our saving grace several times in past projects with Flux Capacitor.

Single threaded by design

As each tracker essentially takes up a single application thread you don’t need to worry about typical concurrency problems. There is no way that messages are processed out of order or ‘at the same time’ by the same tracker. This reduces the complexity of your code and can prevent a lot of hard-to-nail-down bugs.

Message Functions

Now that message tracking has been explained, it is time to explain the different message types handled by Flux Capacitor. We will discuss them one by one.

Queries

Queries are similar to GET API requests, they are questions that give a result (sometimes an exception). We provide you methods to input a query, and receive this result or error easily and in the same manner, whether the answer came locally or from a completely different application. Flux Capacitor automatically passes back results that are meant for the application that originally sent the query. I.e., other applications will not receive those results.

Via our Java client, a query is published when you call FluxCapacitor.queryAndWait(...). This lets the current

thread wait for the answer. There is also an async version FluxCapacitor.query(...) that returns a

CompletableFuture. Query handlers are annotated with @HandleQuery.

If a query (or command) ends in an error we will not only publish the error to the result log but also to a dedicated error log.

Commands

Commands are used to perform actions that typically result in a successful or exceptional response, similar to POST or DELETE requests. Although Flux Capacitor permits a command to be handled by more than one consumer, that is very rare as it could give inconsistent results (what if the one command handler returns successfully and the other an error?).

A command is published when you call FluxCapacitor.sendCommandAndWait(...). There is also an async version, and

the method FluxCapacitor.sendAndForgetCommand(...) for when you are not interested in the result. Command

handlers are annotated with @HandleCommand.

Like with queries, we automatically publish results and errors for commands as well, including ‘empty’ results upon a successful handling of the command.

Events

Events are published to indicate that ‘something’ happened. Quite often an event is published as side effect, when a command was handled successfully. As all events are ‘publish and forget’ the successful results of event handlers are not logged. If an event handler errors however, the result will be written to the error log for debugging and auditing.

Typically, there are two forms of events:

- events about a certain entity, like a shop order or a customer (also called domain events)

- ‘application’ events that are published outside the context of an entity

Both these events will be available for all event consumers. However, the first can also automatically be stored in the event stream of the corresponding entity. This allows you to event-source that entity. More on that in the chapter on event-sourcing.

To publish an application event in Java simply use FluxCapacitor.publishEvent(...). To publish a domain event

please refer to the event-sourcing chapter. To handle any event just add a method to any component

and annotate it with @HandleEvent.

Results

Results are answers to other messages, typically queries and commands.

In Java the return value of a query or command handler method is automatically published as a Result message. Results

are automatically routed back to the application that originally sent the query or command. Results can be handled like

any other message with the handler annotation @HandleResult, though that is quite rare.

Schedules

Schedules are messages that are to be handled sometime in the future. See the dedicated chapter on scheduling messages

Errors

It is often useful to be able to track errors thrown by any microservices connected to Flux Capacitor as well. It makes it easy to audit anything exceptional happening.

You can always choose to publish errors manually, but using our Java client, all errors can be logged automatically. If a handler method completed exceptionally an error is published by default. If your application uses Logback it is also easy to register a Logback appender that publishes console warnings and/or errors to Flux Capacitor automatically.

Errors can be handled like any other message using @HandleError on a method. This is often quite useful too. For

an example, check out the TransferEventHandler class in

our sample of a simple bank application.

Metrics

Metrics are messages that report on the technical operation of your application. Those metrics are stored separate from functional events, as you do not want technical events mixing with functional events. Any interactions between client and Flux Capacitor get automatically logged. For instance, say a tracker of queries just updated its position; this event is stored automatically and will include the consumer and application name, the segments of the tracker and of course the newly stored index.

You can also publish your own metrics by calling FluxCapacitor.publishMetrics(...). Metrics messages can also be

handled with @HandleMetrics. Very useful if you want to e.g., inspect which handler is slowing down your

application.

Event sourcing

Most applications use a database to keep track of the latest state of the application. Getting to that latest state probably involved lots of tiny updates, e.g: a user signed up, an order got shipped, a complaint was filed, and so on.

What if we simply stored all these changes as events? Wouldn’t we then be able to reconstruct the state of the application at any point in time by replaying those events? Well yes: that’s exactly the idea behind event sourcing.

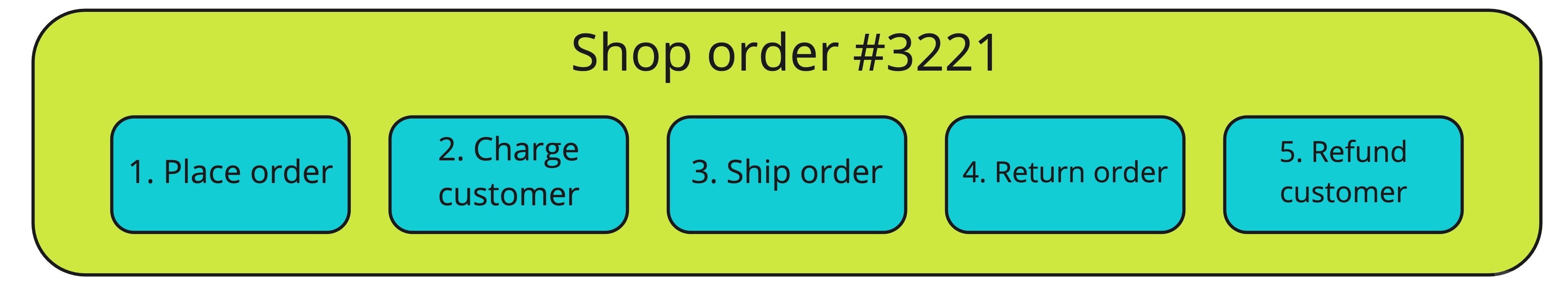

Here’s a chain of events for a given webshop order:

After the dust has settled it almost appears like nothing happened: the customer paid but got refunded, the shipped item is back in inventory, and the webshop got paid but later reimbursed the customer. In reality a lot did happen, but it’s hard to squeeze this entire timeline into a database that only keeps track of the current state.

To fetch the order using event sourcing you would load these events and apply them one by one to recreate the order, i.e: no need to store the order in a database. Event sourcing offers a lot of advantages compared to the traditional way of storing data. For more in-depth explanations please refer to these excellent articles.

Event sourcing in Flux Capacitor

Flux Capacitor doesn’t force you to use event sourcing in any way. It simply makes it easy for you if you do. Here’s how you can load an event sourced entity (or aggregate) using our Java client:

class OrderCommandHandler {

@HandleCommand

void handle(ShipOrder command) {

FluxCapacitor.loadAggregate(command.getOrderId(), Order.class) //load the order entity

.apply(new OrderShipped(...)); //apply a new event

}

}

In this example we ask the Flux Capacitor client to load an order entity when a handler receives a command to ship an order. We then apply a new event to this entity, called OrderShipped. That event will be appended to the event log of the order entity. The next time the order is event sourced the new event will be returned as well. Flux Capacitor will also add the event to the global event log, so any event consumers will also get this event.

How does the Flux Capacitor client know how to apply the OrderShipped event on the Order? Also this part is very easy:

@Aggregate

class Order {

String orderId;

OrderDetails details;

boolean shipped;

...

@ApplyEvent

Order handle(OrderShipped event) {

return this.toBuilder().shipped(true).build;

}

...

}

As you see we leave all the business logic up to you. We tackle generic technical challenges like event sourcing, so you can focus on what’s actually important in your business.

What if you don’t want to event source this entity but store and load this entity the traditional way? That’s easy too:

just change @Aggregate to @Aggregate(eventSourced=false) and we’ll automatically store the latest state of the

entity in Flux Capacitor’s key value store. Boom!

Upcasting

Event sourcing your entities is very powerful, but it comes with a challenge: your stored events need to stand the test of time. They need to keep up with all the changes you make to your event classes, like changing a field name. Flux Capacitor makes it easy to deal with these sorts of changes.

Before deserializing any stored value Flux Capacitor will first attempt to upcast the value using a chain of upcasters. Upcasters are so called because they transform serialized values to be compatible with the latest revision of the value class.

Say you changed the name of a field in your event class. An upcaster can modify the serialized event payload before the data is deserialized. This all happens in your application at the client side; the messages stored in Flux Capacitor Service are not modified.

To mark a change in the revision of a message payload simply annotate its class:

@Revision(1)

class UserCreated {

String userId; //renamed from id

...

}

Assuming that you’re using the default JacksonSerializer, here’s how you would write an upcaster for the change:

class UserUpcaster {

@Upcast(type = "com.example.UserCreated", revision = 0)

ObjectNode upcastUserCreatedTo1(ObjectNode json) {

return json.rename(...);

}

}

This upcaster will be applied to all revision 0 events of the UserCreated event. After upcasting, the revision of the serialized event will automatically be incremented by 1.

Scheduling messages

Another notoriously tricky problem in a distributed application is the scheduling of future events. Typically this would involve an intricate master-slave setup with synchronization on a database, but with Flux Capacitor it is as easy as sending and handling any other message. Scheduled messages are stored and read like other messages except that they are not released before their deadline and can be cancelled.

Here’s an example of a handler in Java that asks a customer if they are satisfied with their order 2 days after it got shipped:

class OrderFeedbackHandler {

@HandleEvent

void handle(ShipOrder event) {

FluxCapacitor.scheduler().schedule("OrderFeedback-" + event.getOrderId(),

Duration.ofDays(2), new AskForFeedback(...));

}

@HandleSchedule

void handle(AskForFeedback schedule) {

... //send an email to the customer

}

@HandleEvent

void handle(ReturnOrder event) {

FluxCapacitor.scheduler().cancelSchedule("OrderFeedback-" + event.getOrderId());

}

}

In the example above you can see that the schedule can be easily cancelled, in this case if the customer returns the order before those 2 days are up.

Full behavior testing

Full behavior tests of your service, especially tests across multiple services, are normally quite difficult to achieve. Often a local environment has to be created with complete service setup. This requires a (mock) database, fully running services and at least some networking. These integration tests are often very slow to run, and therefore not used as primary means of testing very often. Most services have just one or two if any, just to detect problems to load the application and check connections between application components. Any functional testing is usually done only in isolated unit tests running against mocks.

In practice that means that the functional behavior of your entire application is often not being tested.

Unit tests are inferior to behavior tests. Unit tests are expensive to maintain and make your application inflexible. Most times when unit tests fail there was no actual change in behavior, but some technical change. A piece of code might have moved from one component to the other, and now both unit tests of these components are failing. The bigger the change, the more difficult it is to change unit tests. When you only use behavior tests, with actual customer behavior as input and output, your tests will always be green, as long as you did not change any behavior. You might search a bit longer to find the responsible component, but it scales much better.

With Flux Capacitor we support full behavior tests that run as fast as any unit test so you don’t have any of these problems. We supply an easy to use given-when-then test framework. Here’s an example from our banking sample project:

class BankAccountTest {

...

@Test

void testCreateAccountTwiceNotAllowed() {

testFixture.givenCommands(createAccount).whenCommand(createAccount)

.expectException(IllegalCommandException.class);

}

@Test

void testTransferNotAllowedWithInsufficientFunds() {

testFixture.givenCommands(createAccount, createAnotherAccount)

.whenCommand(transferMoney)

.expectException(IllegalCommandException.class).expectNoEvents();

}

}

Of course, we also made it easy for you to load a test version of Flux Capacitor via docker. That way you can test your entire microservice setup in one go. You can find this fully functional test server on Docker Hub.